More on Bloom filters

The problem

Given a large set of elements, how can we answer queries about set membership in

- Constant time

- Small space

- Small margin for false positives

Let be a set in universe on which we which to answer queries of the form Does ?

Bloom filter (BF) is an extremely simple solution to this problem. They have been widely adopted in network routers, web caches and packet inspection. Bloom filters are also at work in Uber’s M3 platform, Blockchains and URL shortning service Bitly. In the past Google Chrome used Bloom filters to detect malicious URLs but have now moved on to use Prefix-Set.

Solution: Standard Bloom filter (SBF)

Take a bit array of size . Let be a family of k independent hash functions such that is an integer in . For every element in , get k indices using all functions in and set those indices to 1 in our bit array. If a bit is already set to 1 by previous element, do nothing.

To check if an element , obtain k indices using .

if and only if the bit is set to 1 at all k indices i.e

.

It is easy to see that this construction leaves the possibility for false positives. and may be set to 1 by distinct elements and . Probablity of false positive is given by

Derivation is straighforward and can be easily found online. Wikipedia

Interesting Fact: Instead of k hash function, we can start with two independent hash functions and and generate other hash functions using without any loss in asymptotic false positive probability. More details here [5]

Problem with SBF

Bloom filters perform well when the set is static. For many real world applications, this is not the case and changes over time with addition and deletion of elements, example routers monitoring network flows witness new connections being established and others getting closed.

Deletion of elements from the set may lead to False Negatives in a Standard Bloom filter.

The reason is self evident. If we set for while deleting , we may also be setting where for some . Subsequent membership queries for will wrongly output false. This has prompted researchers to come up with several solutions which allow delete operation in a BF. Three of these are discussed below.

Solution: Counting Bloom Filter (CBF)

We can make a small change to bit array to overcome the problem of false negatives on deletion. Instead of creating a bit array, each cell becomes an n bit counter. When gets hashed to a cell, we increment the counter by 1. For deletion, each is decremented by 1. A query is believed to be in the set if all are greater than zero. Probability of false positives remain the same as a SBF. The size of counter is usually 4 bits. The probability of overflow with 4 bits is extremely low [1]

Problem with CBF

Each cell in a CBF takes up 4 bits even though most of the values are zero. We can see that a CBF has poor utilization of space and reaches atleast 4x the size of a SBF.

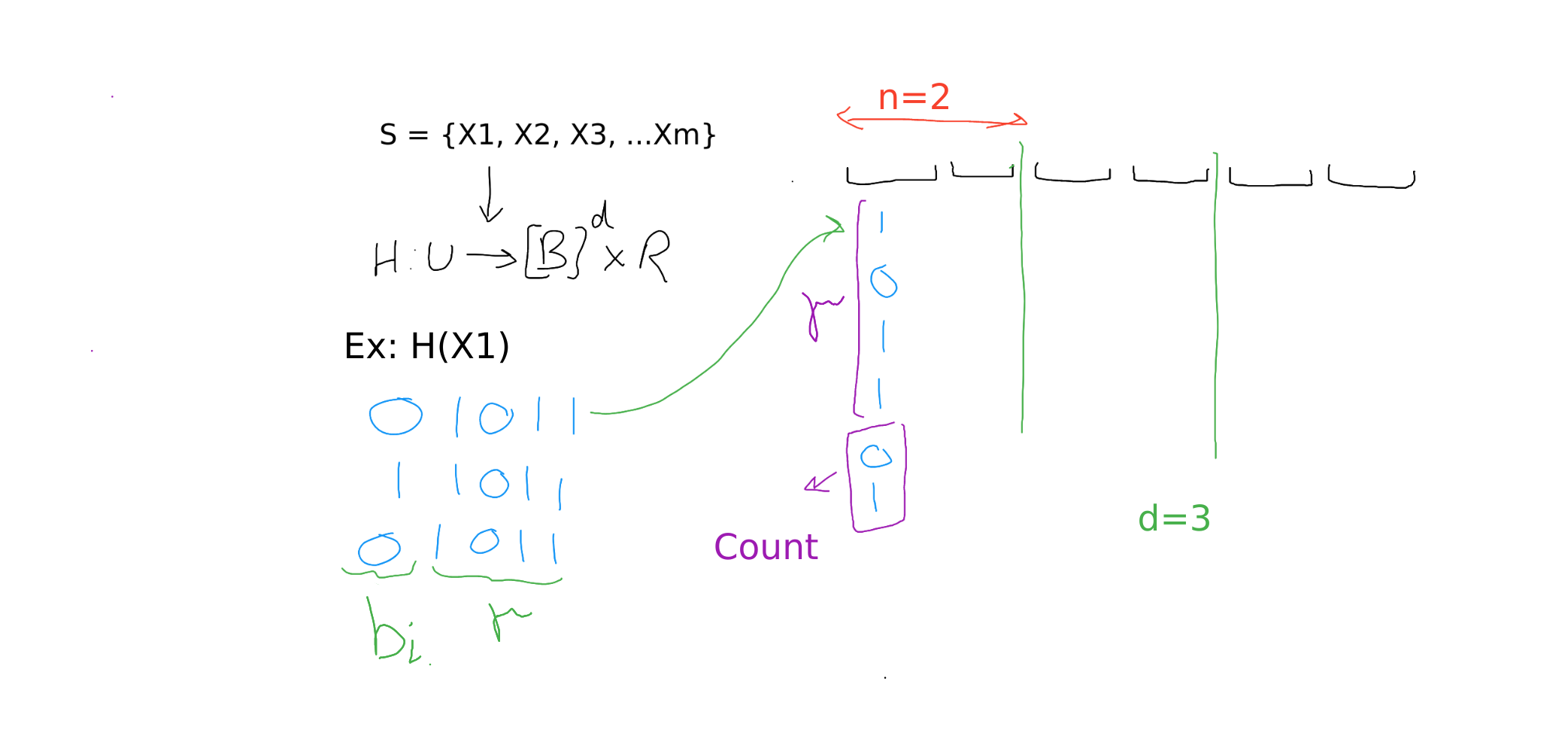

Solution: d-left Counting Bloom Filter (dl-CBF)

d-left hashing is an “almost perfect” dynamic hash function [2]. We need a dynamic hash function because elements can be added and deleted from our set and a static hash function does not perform well for a changing set.

Steps for dl-CBF construction:

- Take a hash table with buckets. Each cell in a bucket stores a fingerprint and count.

- Divide the hash table into subtables. Each subtable has buckets.

- For each element in the set, use hash function of the form

- Let

- denote bucket index where .

- is the fingerprint of size bits.

- Search buckets to see if exists in any bucket. If yes, increment the count of that cell.

- If the fingerprint is not found, select the least loaded bucket from our choices. If two or more buckets have the same load, select the left most bucket to add the fingerprint.

- Let

Always-go-left is a biased choice in case of clash. This may seem counter-intuitive to our objective of balancing load uniformly across buckets. Curious readers can read this [2] interesting paper.

{1011} is fingerprint of which is put into the first bucket since it was the left-most least loaded

{1011} is fingerprint of which is put into the first bucket since it was the left-most least loaded

To check membership of an element , get its target using the hash function and search buckets parallely. If is found, we say

To delete an element, we follow similar procedure to CBF. Use the hash function to find the bucket which holds and decrement the count.

Comparision with CBF: Since elements are finally hashed to bits (after choosing the bucket) instead of a single index in CBF, the probability of collisions in d-left hashing is very low (upper bounded by ). This allows us to have smaller 2 bit counters as compared to the 4 bit counters necessary in CBF to prevent overflow. Experiments by Bonomi et.al [1] reveal that

- dl-CBF of the same size as CBF achieves 100 times smaller false positive probability.

- For the same false positive probability, dl-CBF utilizes half the space of a conventional CBF.

Probability of False positive

Result is easy to derive. Refer to [1] for more details.

Cuckoo Filter (CF)

A Cuckoo filter is based on Cuckoo Hashing. It is a simple yet powerful algorithm which can achieve upto 95% utilization of the hash table. It it 3-4 times more space efficient than a CBF and upto 2 times more space efficient than a dl-CBF.

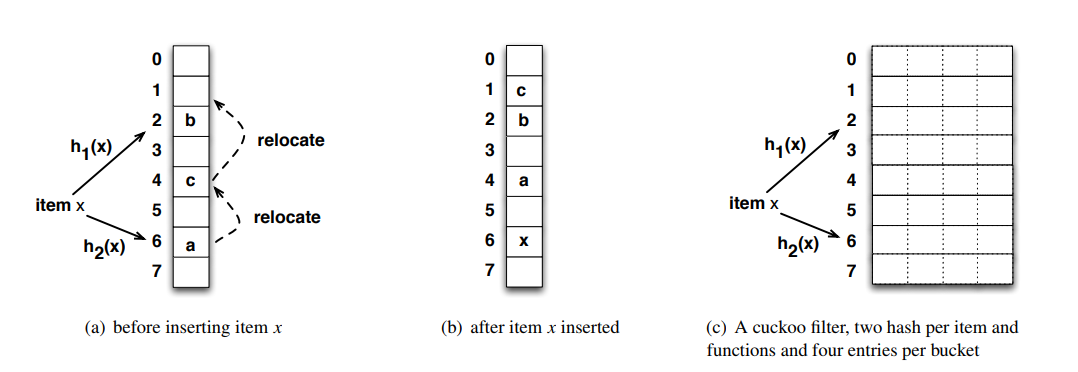

Cuckoo Hashing: We start off with a hash table with n buckets. For every element to be added to the hash table, we have two buckets to choose from. These two buckets are dervied from two hash functions and . If either of the two buckets is empty, we insert into that empty bucket. If both are occupied, choose either one and move its element to its alternative bucket in the table.

An illustration of Cuckoo hashing. is hashed to the buckets containing and . We move to its alternate position to accomodate . At ’s alternate position, is already present. is moved to its alternate position to make space for . Source [4]

An illustration of Cuckoo hashing. is hashed to the buckets containing and . We move to its alternate position to accomodate . At ’s alternate position, is already present. is moved to its alternate position to make space for . Source [4]

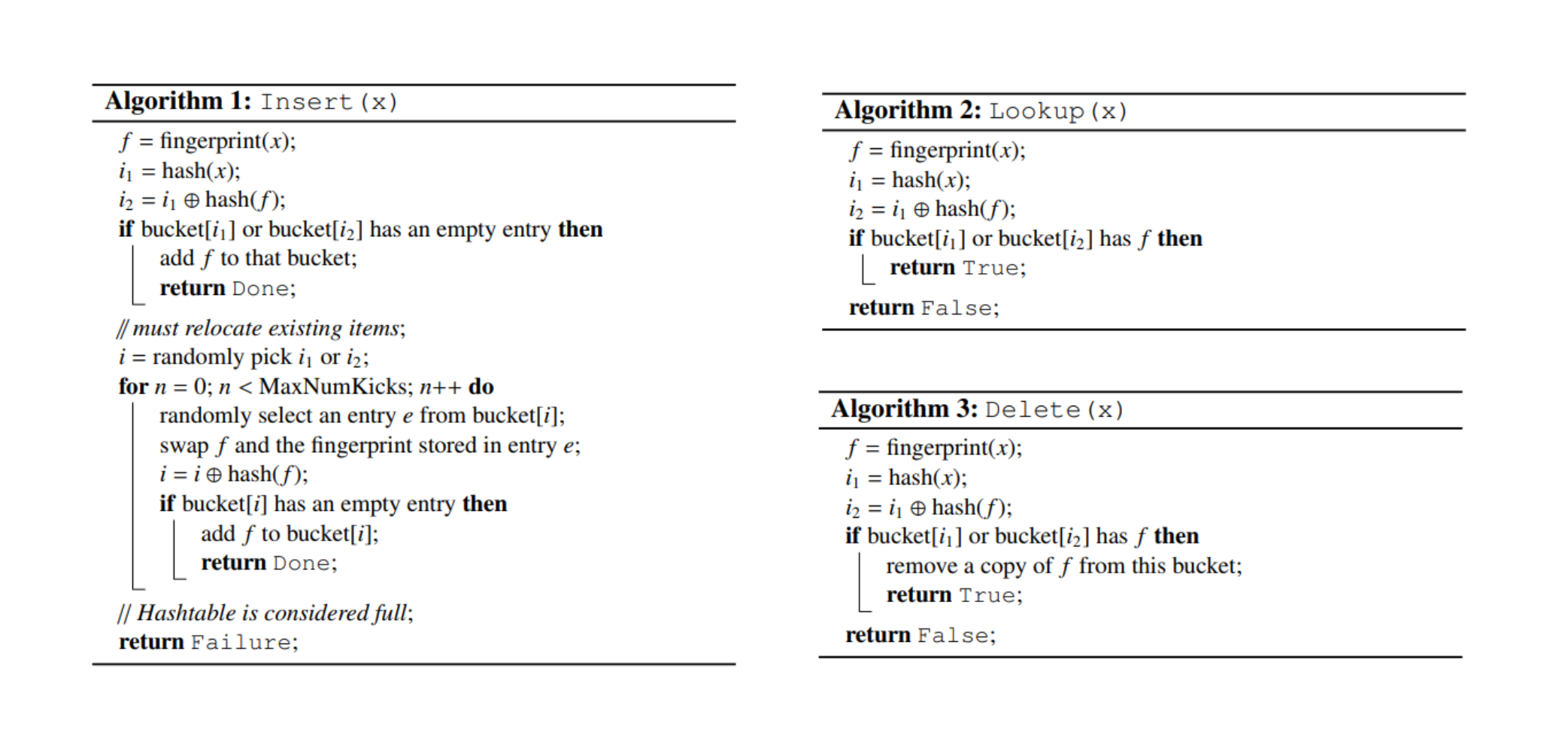

Some changes to the standard Cuckoo Hashing technique are required to make it work as a set membership datastructure. Instead of storing the element as it is in the hash table, we store fixed length fingerprints. This helps us save space but also leads to another issue. In the image above, when wants to take the place of , we need to calculate the alternate bucket for . This means we need access to the element so that we can calculate its alternative position or . Since we are only storing fingerprints, we need a way to calculate the new bucket index without access to the original element itself. This is accomplished by a simple idea. Two candidate buckets are calculated as following:

If we have to move an element in bucket , we can calculate its new position with the help of XOR operation

There is a trade off between table occupancy and size of fingerprint. If we want higher table occupancy, we have to increase size of fingerprints to maintain the same probability of false positives. We need larger fingerprints to reduce probability of collisions.

Algorithms to insert, lookup and delete elements from a Cuckoo filter. It is relatively simple once we grasp Cuckoo hashing and the 2 modifications discussed above. Source [4]

Algorithms to insert, lookup and delete elements from a Cuckoo filter. It is relatively simple once we grasp Cuckoo hashing and the 2 modifications discussed above. Source [4]

Summary

We looked at 3 different variants of the Standard Bloom Filter (SBF) which handle deletion of elements. Counting Bloom Filter (CBF) is extremely simple in construction but it has very poor utilization of space. With some added complexity, d-left Counting Bloom Filter (dl-CBF) improves upon CBF by using d-left hashing and storing element fingerprints to save space and reduce probability of false positive. Finally, Cuckoo Filter goes further in saving space by getting rid of counters. There are alse other variants of Bloom Filter such as Bloomier Filter or Quotient Filter and it is upto the user to evaluate which is best suited for their application.

References

[1] F. Bonomi, M. Mitzenmacher, R. Panigrahy, S. Singh, G. Varghese, “An improved construction for counting bloom filters”, Proc. ESA’06, pp. 684-695.

[2] Vöcking, Berthold. “How asymmetry helps load balancing.” J. ACM 50 (2003): 568-589.

[3] Rasmus Pagha, Flemming FricheRodler “Cuckoo Hashing”, Journal of Algorithms, Volume 51, Issue 2, May 2004, Pages 122-144

[4] Fan, . Cuckoo Filter: “Practically Better Than Bloom”. Proceedings of the 10th ACM International on Conference on emerging Networking Experiments and Technologies

Pages 75-88

[5] Kirsch A., Mitzenmacher M. (2006) Less Hashing, Same Performance: Building a Better Bloom Filter. In: Azar Y., Erlebach T. (eds) Algorithms – ESA 2006. ESA 2006. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 4168. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg